It had a soul which lay in the darkness and it was their task to seek it there

Lecture III 16th May, 1941

In the last lecture we began considering the evidence, which is to be found in the writings of the old masters, as to the attitude which the art demands from its adepts.

We will continue this subject today.

The next passage is from the “BOOK OF KRATES, a text which has come to us through the Arabs, but which, judging by its subject matter, certainly dates back to Alexandrian times.

There is a dialogue between an adept and an angel.

Such dialogues are by no means rare in the alchemistic literature, the philosophical content is often depicted in the form of conversations.

There is even a famous classic, the “Turba philosophorum”, which is written in the form of a supposed meeting of all the old Greek philosophers to discuss the secrets of the art.

In our passage from the “Book of Krates” it is an angel who is interviewed by an “artifex” (an artist) , that is, by a philosopher who, we are told, was a “pneumatikos” (a spiritual man).

He says in the course of his conversation with this angel:

“He who belongs to the spiritual people is bent on having books and seeks them, and he will make it his duty to strive with mind, soul and body to propagate the ideas which they contain. When he discovers something clear and precise in them, he gives thanks to God. When he meets a point which is obscure, he strives with the help of his studies to get an exact conception of it, in order to reach the goal which he has set himself, and to act accordingly.”

The angel, smiling, answers Krates:

“Your intentions are excellent, but your soul will never decide to hand out the truth to the people, on account of the diversity of opinions and the wretchedness of ambition.”

We hear in this text that Krates, the “pneumatikos”, has the idealistic intention of preaching the truths that he has realised, of spreading abroad his philosophy among the people.

But the angel smiles in his superiority at this idealism, as if it were too optimistic, and says that, though the intention is excellent, Krates will never decide to spread abroad the truth among the people.

And this for two reasons:

I. Because of the differences of opinion: if Krates should announce his truth, such a terrible quarrel would break out, that his small amount of enlightenment would be torn in shreds during the discussion, and trampled in the dust.

II. Because of the wretchedness of ambition: when someone has picked up a little of this truth, he is tempted to adorn himself with borrowed plumes, to assume an air of importance and thus to deceive himself.

For the truth these philosophers are seeking is intended to change the philosopher himself in some way ; so that in reality there is no tendency to spread abroad formulations of the truth, because the philosopher is aware that in doing so he would simply be handing the task of transformation to other people, instead of facing it himself.

This text is very profound.

When Krates had finished this conversation with the angel, the latter vanished and refused to return, and the text goes on to tell us how Krates behaved in these circumstances; in other words: what a philosopher must do in order to induce his angel to return to him:

” . . . In order to induce God to send the angel again, Krates persists in contemplation, fasting and prayer.”

This is a purely religious exercise as you see. This relationship to an “angel”, as you will hear again later, occurs fairly regularly in old alchemy.

The old masters often speak of a “spiritus familiaris”, a familiar or helpful spirit, who stood by them in their work.

You find such spirits being invoked in Faust, that genuinely alchemistic work, the spirit of earth, for instance.

The familiar spirit is called the “paredros” in Greek, the one who stands by.

The spirits of the planets are most often invoked, particularly those that dominate the alchemist’s horoscope.

It was Saturn, above all, that could make men skillful in practising the art.

In another treatise, called the BOOK OF OSTANES, which also comes to us through the Arabs though it is of antique origin, we read that:

“It is only possible to work on the stone with resignation, science and intelligence ”

It is remarkable that all these Arab authors (Abul Qasim and such people, for instance) lay a great deal of emphasis on intelligence.

Knowledge and intelligence are by no means identical, as you know; there are many people who know a great deal, who labour under loads of information, without being at all intelligent.

The next quotation is from the “Liber de compositione alchemiae” which is said to be of Arabic origin. It is in Latin and may possibly come from the eighth century.

An old alchemist, called Morienus, appears in this treatise, both his actions and words are recorded.

We read in this book:

“He who does not possess the gift of patience should leave this work alone.”

This work is concerned with a peculiar transformation of the soul, a strange psychical process, and these words of Morienus agree exactly with the well-known words of St. Ambrose:

“In patientia vestra habetis animas vestras.” (In your patience you possess your souls.)

The man who applies himself to this work, if he can only have sufficient patience, will gain possession of that which is uncontrolled in other people.

Another old master (whom it is impossible to date accurately, though we find traces of him as far back as the twelfth century), ALPHIDIUS, says:

“If thou art be humble thy wisdom will become perfect; if not, the disposition will remain concealed in thine innermost.”

This sentence shows us that the origin of the alchemistic work is not in the substances used in the opus, but in the soul of the worker.

Alphidius says in another passage:

“Know thou, that thou canst not have this science, unless thou consecratest thy mind (mens) to God; that is, if thou dost not destroy all corruption in thine heart.”

Here again a most earnest moral and religious attitude is strongly emphasised.

In the same text, on the same page, we read:

“I have left all pleasures behind me, and have besought God to show me the pure water (aquam mundam).”

This pure water is the chief instrument of the art of alchemy.

It is the water of life which, as you will remember, is a term also applied to Christ.

In another treatise, the so-called “Epistle of Aristoteles”, we read:

“May divine providence help thee to conceal thy purpose. One should have foresight and recognise the devilish illusions, and protect oneself against them from the beginning, for the devil is fond of meddling in the chemical procedure.”

We have another reference here to a special devil who meddles in the alchemistic opus, a chemistry devil, apparently particularly connected with the work, and who finds great pleasure in disturbing the serious alchemists while they are working.

In other words: the alchemists must expect to come into conflict with their own unconscious during this work, the unconscious will attack them, and cause exceedingly disagreeable emotional disturbances and even illusory visions.

We come now to one of the most curious texts in old alchemy, the AURORA CONSURGENS, which I have often mentioned before.

It has of local interest for us, in that we have a unique and most beautiful manuscript copy of it in Zurich, the Codex Rhenoviensis, a fourteenth century manuscript which comes from the monastery of Rheinau.

Unfortunately it is not complete, four chapters are missing, as I told you last Semester.

There is a more complete though later text (also a manuscript) in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.

This work is extremely interesting, in that it teaches us a great deal about the psychology of alchemy.

The first part is written in a dreamy, ecstatic style, whereby a great quantity of psychological material gushes out like lava.

It is, however, very difficult to understand, and the text is in rather bad condition.

The beginning is extraordinarily different from the end; the second part is very objectively written, and it is possible that the two parts are by different authors, for the first part is certainly a kind of ecstatic avowal.

One often does not know who is speaking, it is as if many voices mingled.

The first part must have been written by a cleric, the sentences consist of one Vulgate text after another, but it contains ideas which are extraordinarily interesting as to the inner psychology of the alchemistic work.

The text is called: “AURORA CONSURGENS” or “AUREA HORA” (the rising dawn or the golden hour).

We read there:

“If thou wouldst conquer, learn to endure.”

The virtues are speaking and patience says this .

Later the apostle says:

“Be patient for the Lord draweth nigh.”

This is a paraphrase of James V. 8:

“Be ye also patient; stablish your hearts: for the coming of the Lord draweth nigh.”

This means in other word : the fulfilment of the goal of the alchemistic opus (the production of the mysterious substance) can evidently be expressed as if it were the “drawing nigh” of God himself.

This reminds us of the Mass where we also find a passage, before the consecration, in which the Advent of the Lord is announced.

As the author is a cleric, it is not unlikely that he smuggled in certain contents of the Mass.

For the Mass itself is an “opus” (the Benedictines themselves use this term), it is a work of transformation, and is therefore similar to the alchemistic procedure.

Undoubtedly the Mass did directly influence the later medieval texts, we can easily prove this; but it is doubtful. to say the least of it, in the case of the older texts, because the liturgy of the Eucharist was not yet in existence.

The alchemistic opus is older than the Mass, just as the eternal water of alchemy is older than Christian baptism.

The divine water is mentioned in texts (which are Pagan and had no connection with Christianity) in the first century A.D..

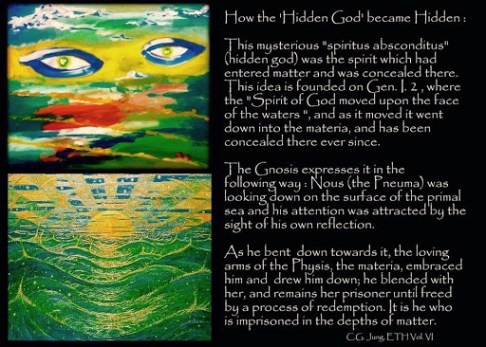

We can hardly say that it is the author who speaks in the first part of the text, it is rather a most mysterious being, which could be described by the Latin term “spiritus absconditus” (concealed spirit): the spirit of Mercury or Hermes.

Hermes is the old Psychopompos, a mystagogue (teacher of the initiants), and the Poimandres (shepherd of men).

These terms are of pagan origin, but there is also such a figure in an early Christian text: “The Shepherd of Hermas.”

This mysterious “spiritus absconditus” was the spirit which had entered matter and was concealed there.

This idea is founded on Gen. I . 2, where the “Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters”, and as it moved it went down into the materia, and has been concealed there ever since.

The Gnosis expresses it in the following way:

Nous (the Pneuma) was looking down on the surface of the primal sea and his attention was attracted by the sight of his own reflection.

As he bent down towards it, the loving arms of the Physis, the materia, embraced him and drew him down; he blended with her, and remains her prisoner until freed by a process of redemption.

It is he who is imprisoned in the depths of matter. The “spiritus absconditus” is not really in the materia, that is only a projection, he is of course in ourselves.

It is the unconscious, which appeared to earlier, more naive people in the materia, in objects.

This still happens to us today, not, however, in the form of beautiful and great images but rather in silly little things.

When two people have a quarrel, for instance, they say to each other the things they should say to themselves.

We see the mote in our brother’s eye but not the beam in our own, and these projections can happen with impersonal as well as personal images.

The way in which the “spiritus absconditus” speaks through the author of the first part of the “Aurora consurgens”, reminds one of the spirit of earth in Faust: this spirit speaks to Faust, who writes down what it says.

The author of our text continues later:

“Turn to me with your whole heart and do not spurn me because I am weak and black, for the sun has changed my colour (A) and the depths have hidden my countenance, (B) and the earth is corrupted and infected (C) in my operations, because darkness had been laid upon it. (D) Because I am held fast in the mire of the deep (E) and my substance is not revealed, therefore I cried out of the depths and from the abysses of the earth doth my voice speak unto you.”

This passage consists entirely of texts from the Vulgate: (A) refers to the “Song of Solomon” I:5 & 6:14 “I am black, but comely, 0 ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar, as the curtains of Solomon. Look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me . . . ”

It is the loved one, the bride, who speaks thus in the Song of Solomon.

This “spiritus absconditus” is often represented as feminine, and in a very peculiar form: above she is a beautiful virgin with a crown, and below a snake, the so-called Edem, a Gnostic idea, and really that same Physis who caught Nous in her loving arms.

(B) refers to Jonah II: 3-6:

“For thou hadst cast me into the deep, in the midst of the seas; and the floods compassed me about: all thy billows and thy waves passed over me . . . The waters compassed me about, even to the soul : the depth closed me round about, the weeds were wrapped about my head. I went down to the bottoms of the mountains; the earth with her bars was about me forever . . .”

This is a very beautiful description of this “spiritus absconditus”, the spirit which is concealed in the depths of the water, and which has sunk down into the darkness of matter.

(C) refers to Psalm 106

” . . . The land was polluted with blood. ”

and (D) to St. Luke XXIII: 44

” . . . and there was a darkness over all the earth until the ninth hour . ”

There is evidence in the text of the “Aurora Consurgens” itself, that it is really these Vulgate texts which are quoted indirectly, so the connection is no arbitrary one.

The author often says: “Jesaias dicit” (Isaiah says) or “Apostolus dicit”, so that one then knows for certain that it is these passages which are meant. It is interesting that during the Crucifixion the darkness coincides with the death of Christ, that is the moment when Christ went into the darkness.

(E) refers to Psalm 69:2: ” sink in deep mire where there is no standing” and

(F) to the famous verse in Psalm 130: 1-2 : “Out of the depths have I cried unto thee, 0 Lord. Lord, hear my voice: let thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications.”

The language of this text shows clearly that the work on their art was an entirely religious experience for these old philosophers.

They even sometimes felt that the language of the Bible was the most suitable language in which to express themselves, because the subject matter was so similar.

The baffling thing is that, although this whole world of images has nothing whatever to do with natural science, the two always appear together in the alchemistic opus.

But it is just here that we can realise what matter meant to these people, they experienced it in a mystical way.

It had a soul which lay in the darkness and it was their task to seek it there.

They were conscious of the fact that they could rescue the darkened God from the materia, or at least this is what they attempted to do.

We come now to a French alchemist of the fourteenth century: DE RUPESCISSA, who had a similar attitude:

“It is our purpose, with the aid of this book, to comfort and strengthen the poor preachers of the gospel (les pauvres hommes evangelisans), in order that their supplications and prayers should not be in vain where this work is concerned.”

The alchemists are referred to here as “les pauvres hommes evangelisans”, the poor people who make known the message, who preach the gospel.

The author draws another direct parallel here, between alchemy and the Christian religion.

We will now take a small leap forward in time, and come to the famous sixteenth century alchemist, H. KHUNRATH.

As I told you before, in common with the majority of medieval alchemists, Khunrath was a doctor and a very learned man.

On the subject of attitude, he says:

“It is not our avaricious design, self-will, activity devoid of vocation, diligent reading of worldly wisdom, study and slovenly experimenting on which it solely depends, but it is far more God’s calling, his will and his grace. This is the reason why so few of you attain the art. It is impossible to reach this art through books alone, or by obstinate labour, or even by both at once and together, however diligently one tries, and whatever one’s ability and desire.”

We see here that the study of books and the work on the opus (both warmly recommended by all the alchemists) do not of themselves lead to the goal of the art.

Khunrath continues:

“Shouldst thou discover in thyself (with a true philosophical renunciation of all transitory things which the world values) a p articular inclination, a rightful passionate longing, a fervent love, a strong desire and an inner urge towards the chemical art – but not in order to heap up gold and riches or to accumulate great treasures after the way of Mammon, but rather with the hope of realising the Magnalia of the great God, and of using its fruits theosophically – then, without doubt, thou art conditioned, disposed, called and sent by God. Now pray and work as advised, and thy labour will not be in vain.”

Such a man is an “electus”, a chosen one, who is able to bring this art to its conclusion.

“To sum up: In this case, without the special support and assistance of Ruach Hhochmah-El, the god of divine wisdom, or of other sub-delegated go od spirits or angels sent by God, our theorising and practising are in vain.”

Here again we are told, that the goal of this art can only be reached when a direct intervention of the Deity takes place, that is, through the Grace of God; God sends a delegate, an angel, to complete the work, to produce the stone.

Psychologically this means that, to reach the goal, a phenomenon must take place, of which one can only s ay that it is a personification, or an autonomous appearance, of the unconscious spirit.

The “spiritus absconditus” must, so to speak, appear “in figura”, as the “paredros”.

This is very difficult for us to understand, but such an idea presented no difficulty to medieval man, for he was completely convinced that the psyche was of an autonomous nature.

We are very vague about the psyche, we have a dim idea that it is a sort of vapour arising from the warmth of the brain or a mere result of psychological functions.

The modern attitude towards the psyche always reminds me of an old text book, for the medical corps of the Swiss army, which said that the brain was like a dish of macaroni.

Presumably the psyche was the steam rising from the macaroni!

According to the spirit of that time, the psyche was an epiphenomenon of the physical.

We should really b e willing to confess that we are quite ignorant of the nature of the psyche; though unfortunately we do know that it can act in a very independent and unexpected way and produce phenomena which are impossible to explain rationally.

With all our modern means of disinfection we cannot rid ourselves of our fears, and is not the history of the world made by factors far beyond man’s conscious intentions?

The s e factors are of a psychical nature, yet we go on thinking that the psyche is a vapour.

To call the psyche an epiphenomenon, or to identify it with human consciousness, is equally foolish.

Consciousness is also a psychical phenomenon, but it swims on the great unconscious, as it were, and we shall never know what the unconscious is, for it is the unconscious, the unknown, the “spiritus absconditus”.

With what could we comprehend it?

Only with itself, because we can never get outside the psyche.

For it is the Ouroboros, it always eats its own tail, it is an inescapable vicious circle.

We are always entirely dependent on what our psyche makes of a thing, on what our brain says about it.

Take cold and warmth as an instance: If we come from a temperature of 20 degrees below zero and touch this table it will seem warm, almost hot, whereas it is a cool surface for other people.

Psychical existence is the phenomenon par excellence, we cannot conceive of any other kind of existence.

Beyond the twelve categories of Kant is the “noumenon”, “das Ding an sich” (thing in itself), the union of the opposites, the Deity.

How can we be sure, then, that anything is what it seems to us, for we are always dependent on a psychical image.

Everything that we touch is psychical; we make wonderful scientific instruments to discover the real nature of things, but in the e!!.d absolute objectivity is always defeated by the fact that everything is psychical.

Old Khunrath was aware of this fact in his own way.

He continues:

“Beloved, hearken to what the philosophers themselves said about their books.

Hortulanus says:

“Hortulanus was also an old master of the art.

” ‘Oho dear reader, if thou knowest how to prepare our stone, then I have told thee the truth, but if thou art not capable of doing this, then I have told thee nothing.’ Geber, Morienus, Lilium and others say the same, that only he who knows how to prepare the stone can rightly and truly understand the sayings of the philosophers.”

So no one understands this art who does not know it already.

“It is therefore most necessary to entreat God, the Lord of Hosts, for the spirit of his wisdom, that he may dispel our darkness and enlighten us with the light of his knowledge and truth, that he may embrace us, overshadow us and fill us with his great goodness, that he may open to us the writings and other monumenta of the philosophers, interpret and expound them, and lead us to understand the light of nature; thus all is well: If thou hast made him”

The spirit of God’s wisdom = the Holy Ghost.

“thy praeceptor familiaris”

The familiar spiritual teacher.

“then all obscure words and hidden things are clear and open to thee. For God from Heaven can reveal all hidden things. Of a truth this is so.”

We see here that for Khunrath the culmination of wisdom is to realise that we know nothing out of ourselves, it must be revealed to us through a kind of miracle.

These old philosophers expected, through their preoccupation with the science, their meditation and contemplation, that they would entice the grace of God to come to them and bring them revelations.

Such an idea (as is often the case with superstition) was not at all stupid.

There is something in such ideas.

We know from experience, that when we are seriously striving to achieve something, all kinds of hunches come to us about it, and a hunch is a small revelation.

The right hunch in the right moment can even save one’s life, and naturally a scientist or student can also get the right hunch at the moment when he is most perplexed.

In German the word for hunch is “Einfall” (dropping in), and we must notice the meaning of the words we use.

These “Einfiille”, or hunches, are phenomena of a spontaneous nature, which we cannot control.

They rise of themselves from the depths of the unconscious, and, under certain conditions, bring us solutions or elucidations which are superior to our everyday consciousness.

And if someone tells us that he was enlightened at the critical moment, it is psychologically right, far more right than if he tells us, that at the critical moment he made the right hunch.

The latter is a definite lie, whereas the former is the truth.

When we say: “Thank God it just occurred to me in time”, we don’t think what we are saying, but psychologically we are right. ~Carl Jung, ETH Lectures, Pages 153-160