Alan Watts – You’re ready to wake up…

https://youtu.be/YFzeCv_WFnY

Pierre-Marie Robitaille – New York Times and Unzicker

Alan Watts – We Put Ourselves In Boxes (Rare Footage)

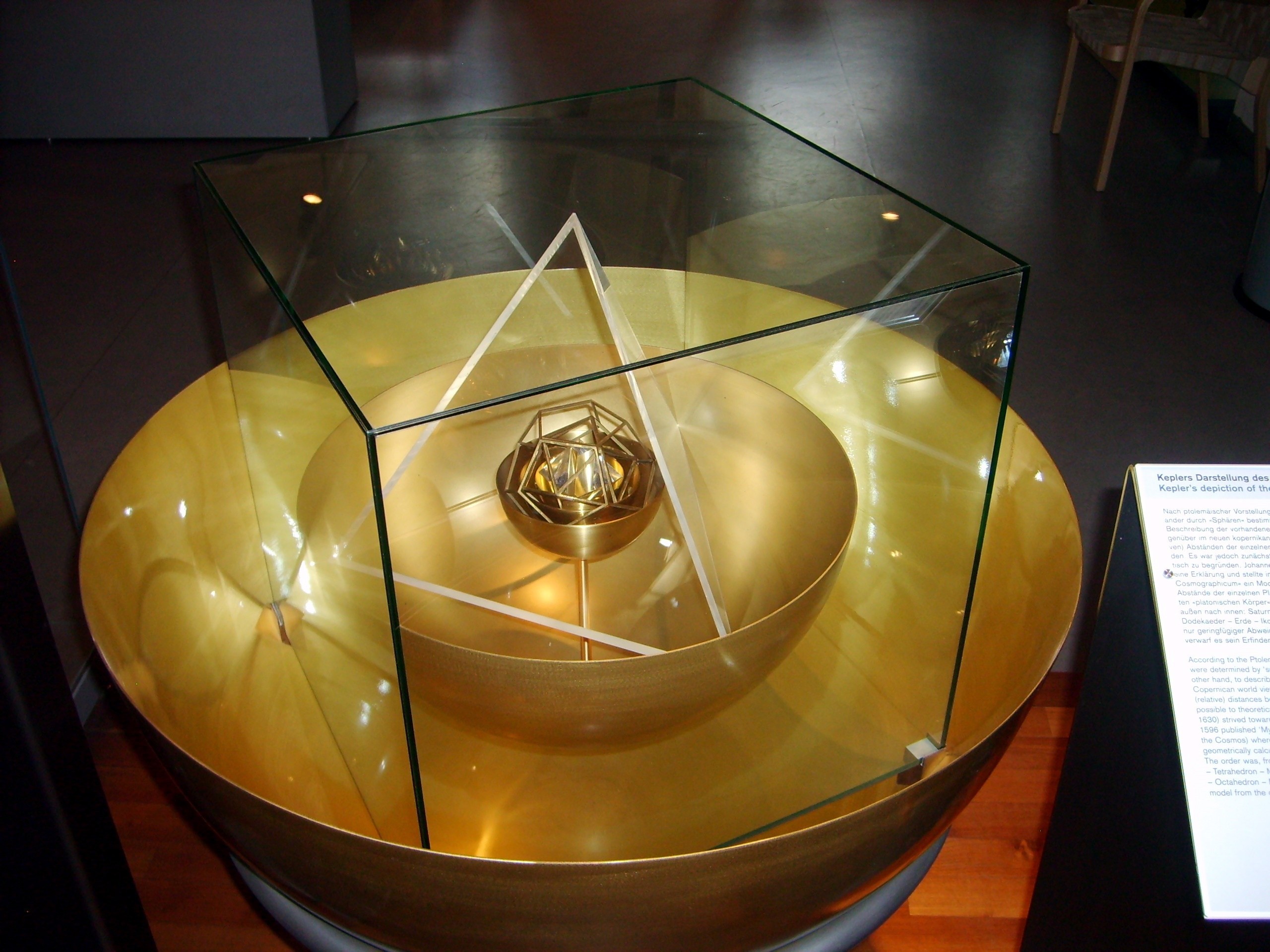

Mysterium Cosmographicum

Platonic Metaphysics, and Time

Technical Hitch – The Logical Indian