Robert Schoch

Easter Island (Rapa Nui; Isla de Pascua) is a tiny speck of land, a mere 64 square miles, in the South Pacific just below the Tropic of Capricorn, 2300 miles west of South America. The closest inhabited land, Pitcairn Island (where mutineers of the Bounty settled in 1790), is over 1200 miles to the west.

The moai, those giant heads and torsos of Easter Island, are emblematic of ancient mysteries and lost civilizations. Viewing them firsthand in all their magnificence during a recent geological reconnaissance trip to Easter Island, I could only be impressed. Carving, transporting, and erecting these inscrutable megalithic statues (some of which are over 30 feet tall and weigh tens of tons) was no mean feat. Surely they reflect a sophisticated society of which we are but dimly aware. Yet, conventional archaeologists have considered the big heads to be, well, big heads— the product of a Stone Age culture that spent its energy carving monotonously stereotypic megalithic monuments as part of some primitive religion, perhaps ancestor worship, or simply as busy work devised by the ruling elite to keep the populace in line on an island from which there was no escape.

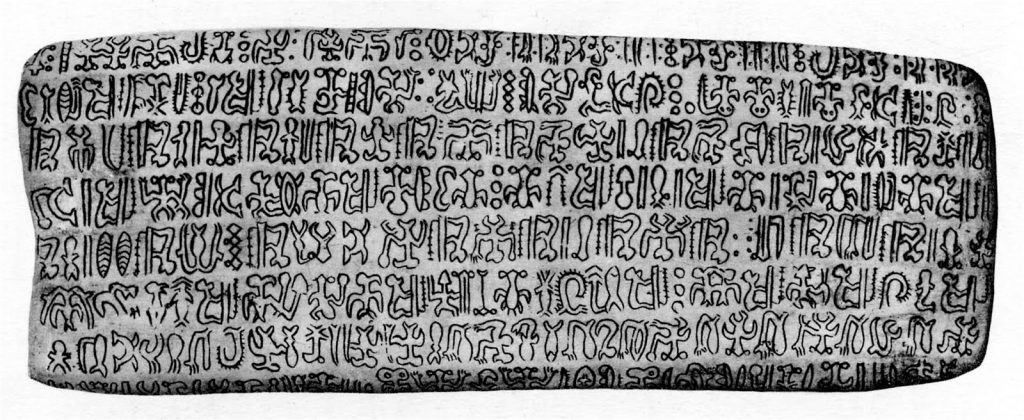

The moai are fascinating, and by applying geological expertise to the problem of their chronology (as I did for the Great Sphinx in Egypt), new light might be shed on the island’s enigmas. I hope to organize a full-fledged geological expedition to the island and pursue such research. But the moai, literally the biggest mystery in terms of their physical size (an unfinished moai still in the quarry is over 60 feet long), are not alone when it comes to the perplexities of Rapa Nui. Though tiny in physical comparison, inscribed wooden tablets have been the subject of curiosity and heated debate ever since they came to the attention of nineteenth century European missionaries.

Numerous wooden tablets covered with a strange hieroglyphic-like script were found in many of the natives’ houses, according to Brother Joseph-Eugène Eyraud, reporting to his superiors in Paris. The writing became known as rongorongo (“lines of inscriptions for recitation”). Unfortunately between the missionaries’ zeal, attempting to separate their new converts from old pagan ways, and internecine warfare, almost all of the rongorongo tablets were burnt or otherwise destroyed. Today just upwards of two dozen remain. Furthermore, those natives literate in rongorongo were killed in fighting, succumbed to disease, or were carried off the island in slave raids. By the late nineteenth century, no one could genuinely read the rongorongo script, and to this day nobody has put forth a convincing decipherment.

Continue reading “Robert Schock – Easter Islands Mystery Script”