As the theory goes; some 14 billion years ago, there was “nothing” focalized in a single, highly-dense point. Then, that “nothing” exploded, hurling the ingredients for everything we see in the universe into existence. On paper, it sounds insane. Heck, its kind of IS insane, but we have several pieces of solid (but not irrefutable) evidence that show not only could it have happened this way, but that it probably did.

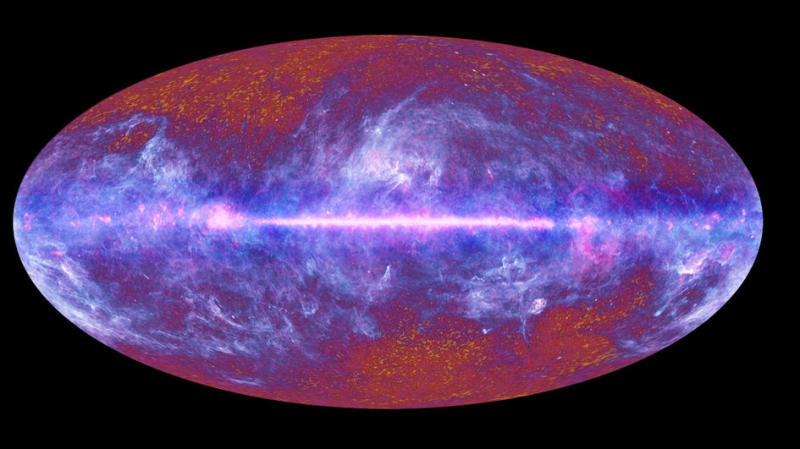

One such proof comes in the form of the “Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation,” (CMB or CMBR) the after-glow of the big bang, if you will. It gives us an opportunity to understand the very first moments following the creation of the universe, yet it also poses many tantalizing mysteries that threaten to unhinge the very fabric on which we believe the universe was formed.

Before we go into those, let’s first explore what the CMBR is. Amazingly, this story has a crappy start.

In 1965, before two scientists, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, started measuring radio signals as they bounced from balloon satellites for NASA’s “Project Echo,” they needed to take preventive measures to make sure the data they collected was completely incorruptible.

The most important (and relevant) task was removing each and every potential source of interference (like radio and television broadcasting signals and those signals emitted from ground-based radars). They also erred on the side of caution by cooling their equipment down to −269 °C (only 4 K above absolute zero) to make sure that heat from the receiver wouldn’t cast any doubt on the veracity of their findings. Given the numerous variables that could go wrong, the men weren’t too perplexed when they heard a low, but steady hum coming from their receiver.

Believing this sound to be a fluke, they once again checked their work; leading them to clean out pigeon droppings that had collected in the antennae they were using, which had been singled out as the primary source of the problem. Once finished, the signal persisted. Moreover, they discovered that it was much stronger than they had originally realized. It was also being emitted uniformly throughout space and it couldn’t be attributed to any object on Earth, or within our galaxy. As it turns out, they caught the first glimpse of the CMBR.

Decades after the background radiation was uncovered, NASA launched the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) to literally probe the CMBR. To put it lightly, the things they found were astounding. Some of those findings included:

- The age of the universe within 1 percent accuracy

- Its composition (the universe is made up of 72% Dark Energy and 23% Dark Matter. “Normal” matter only makes up about 4.6 percent of the over-all mass of the universe).

- The matter makeup was much different in the early universe. Dark matter dominated, but dark energy didn’t exist in high quantities.

- It’s highly probable that the universe is flat in geometry (rather than curved, like Earth)

- Neutrinos, the crazy, shape-shifting particles, are far more numerous than suspected. They also played a significant role in the early development of the universe.

Those findings weren’t all that unexpected, but WMAP (and the newer “Planck”Observatory) found various things that can’t be explained using conventional models. Several of which are,

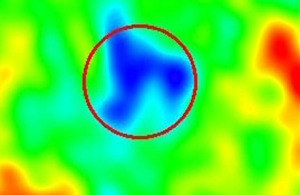

THE CMBR COLD SPOT:

When looking at the data collected by WMAP, scientists noticed that, in one distant region of space — toward the constellation of Eridanus (about ten billion light-years from Earth) — the CMBR showed evidence of a large “hole” in space. They aren’t traditional holes, mind you, but spots where the temperature in the CMBR varies from the usual temperature of 2.7° above absolute zero. One theory attributes this to the existence of a “supervoid.” This would be the largest one in existence, with it stretching out about one billion light-years in diameter. (For the sake of comparison, a void found in the constellation of Boötes — sometimes called the Great Void — extends somewhere between 250 and 330 million light-years in diameter, which makes it one of the largest voids we’ve found so far.)

Interestingly, not only is this region very cold, but it’s also lacking in all types of matter, including normal matter (stars, planets, galaxies and even the most basic material, like gas and dust) and even dark matter itself is strangely absent. Some astronomers suggest that the Eridanus cold spot is merely an arbitrary ‘data artifact’ that means nothing, but the Planck findings cast doubt on that notion. So if it does indeed exist (and it does), how did it form?

Well, the most plausible solution posits that the “hole” was created as CMB microwaves made their way across the universe, to Earth, encountering many regions that (like the hole itself) were lacking in stellar material. The inter-galactic journey through these regions affected them in the opposite way that traveling through hot, dense galaxy clusters tends to inflict on said microwaves. Instead of accumulating energy through the pull of gravity, when they pass through a void, they do not gain additional energy, thus the temperature recorded in the CMB is noticeably cooler.

Now, for some of the more fringe hypotheses: other physicists have suggested that the void is an imprint of a parallel universe. This view *might* supported by the recent discovery of a corresponding void located in the opposite hemisphere of the CMB (at least according to Laura Mersini-Houghton; a noted advocate of the landscape multiverse hypothesis). Another physicist purported that it could be a universe-in-mass black hole (but that claim is dubious at best, even if it would provide a source of all of the missing matter in the universe). The void appears to have shed uncertainty over various standard cosmology models, which say that such large-scale structures (like this enormous void) shouldn’t exist as the universe should be, more or less, the same everywhere we look. Either way, one thing is for sure. When we see such a blatant, huge area that doesn’t fit the bill, notions about the universe get shaken up very quickly and a lot of new questions demand answers.; answers that will be controversial, regardless of all else.

PENROSE’S CONCENTRIC CIRCLES:

The big bang isn’t the only model dealing with the origin of the universe. One of the more fascinating theories centers around an anomaly found in the CMBR. The theory – called “conformal cyclic cosmology“ – was developed by Sir Roger Penrose, a physicist from the University of Oxford. He believes that our universe is not the first, nor will it be the last, universe to crop up from a big bang.

“Conformal cyclic cosmology” suggests that our big bang theory is far too incomplete to be viable. It doesn’t offer an explanation as to why the initial conditions of the universe were geared toward a low-entropy, highly ordered state. That is, UNLESS things were set in motion prior to the “bang” in the big bang. Moreover, when our universe starts to head toward its own end, it will divert back into the universe it was originally, before starting anew. We can thank the general nature of black holes for this, but

But Why?

Well.. As you’ve all probably heard someone say, black holes are the vacuum cleaners of the universe (a claim that is a misnomer, by the way) ; they consume obects that come to close and gradually rid the universe of entropy. Yet they, like all things, eventually meet their end. A lot of things happen in the window of time separating the end from the beginning, like collisions.

When black holes come too close and crash into each other, they releasegravitational waves; a phenomenon that sees spacetime become distorted like ripples in a pond. It has been theorized that the big bang itself should have produced gravitational waves (an assertion that was recently confirmed and then challenged soon after), which could potentially be picked up in the CMBR data, opening the door for us to witness the aftermath if only we knew what to look for. Like, in this case, curling in the polarization of the light in the CMB.

With all of that in mind: as we said before, all temperature variations in the CMB data would be completely random. In yet another example of the opposite being found, Penrose — along his partner Vahe Gurzadyan, who hails from the Yerevan Physics Institute in Armenia — have found several concentric circles in the CMB — places where temperature variations formulate patterns stashed among the warmer regions. They believe these circles are indicative of black hole collisions in the universe that collapsed to form our own (so they are effectively giving us information about the universe before the big bang).

If the men are right, someday in the far, far future — when the universe will no longer be able to expand any further — entropy will digress back to its original state, before the universe collapses in on itself and rebounds, ushering in a new big bang. When that happens, the gravitational waves from our universe might be recorded in the new CMB, allowing a new epoch of aliens to ponder the same questions we currently have no answers to.

DARK FLOW:

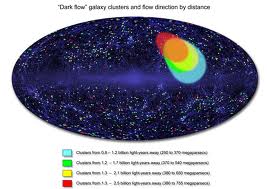

Another anomaly promised empirical evidence that we live in a multiverse (it says that we inhabit one universe in an infinite number of other ones). The CMBR data revealed that more than one hundred galaxy clusters are not only lit up by hot, x-ray emitting gases, but are also speeding off in the same direction, leading away from our solar system (toward the constellations of Centaurus and Hydra).

The clusters seem to be traveling more than 2 million miles per hour, into an expanse of about 20-degrees of sky. Furthermore, the trend is not a statistical fluke, as it continues to hold steady throughout interstellar space instead of bucking black to normal speeds and distributions. Once again, our theories say this should be impossible. The kickback from the big bang should affect galaxies in the same, predictable manner. Especially if the galaxies are moving relative to the faint background glow left behind after the big bang. To get to the root of the problem, WMAP tested this using something called the kinematic Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SV) effect.

Our theories on the CMB basically say that the waves that sprung from the big bang should pass through said galaxy clusters and change in predictable ways under certain scenarios, including if the galaxy is moving relative to the background glow. The WMAP was developed to test this, which is known as kinematic Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SV) effect, but physicists found something else altogether that brought more questions to light than it answered. Learning that“it’s the same flow at a distance of a hundred million light-years as it is at 2.5 billion light-years and it points in the same direction and the same amplitude. It looks like the entire matter of the universe is moving from one direction to the next,” says Alexander Kashlinsky, the team leader of the study from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

As a point of contention, Plank found no solid evidence to support the “preferential direction” part, but given its impact on the validity our measurements, the debacle remains shrouded in controversy. If it does exist, it too could allude to the existence of parallel universes (with both exerting mutual gravitational influence) that bump into our own.

THE “AXIS OF EVIL:”

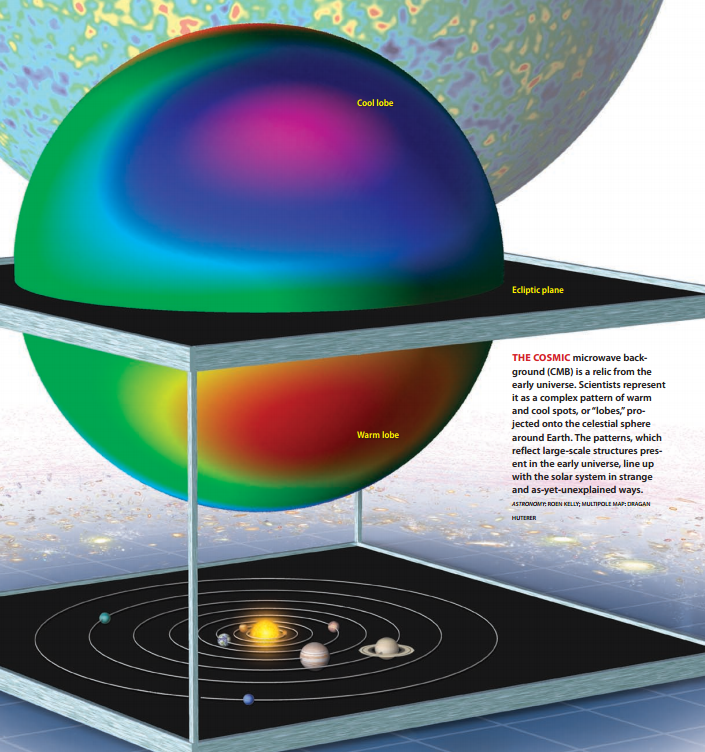

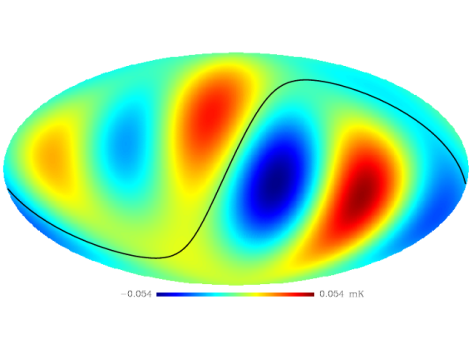

Several years back, astronomers discovered an anomaly that has been given the silliest nickname in the history of physics (maybe with the exception of the God particle): the so-called “axis of evil.” Named as such because of the striking fact that something like this was discovered at all (statistical fluke, or not). First, to reiterate, astronomers know that any variations in temperature in the CMB data should be entirely random; however, in another instance that contradicts that line of thought, NASA’s WMAP showed us that macroscopically, there is an asymmetrical pattern that divides the universe (at least according to the CMB) into two distinct sections, with each side having a different temperature relative to the other.

Of all the anomalies, this one incited the most controversy, with many physicists believing either the axis of evil didn’t really exist, or that it could be explained in an extremely simple manner — perhaps WMAP’s instruments were miscalibrated, or maybe the axis is merely an illusion, mere distortions caused by a nearby supercluster — without having to rework our understanding of anything, but later research seemed to provide a decent amount of support for its existence. In one independent study, led by Damien Hutsemékers of the University of Liège in Belgium, scientists analyzed the light from 355 quasars, looking at their polarization, in particular, seeing that once the light wanders near the axis in question, its polarization inexplicably becomes more ordered, with it seemingly ‘corkscrewing’ around the axis.

In another investigation, when observing 1660 spiral galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, an astronomer noted that the axes on which galaxies rotate also seemingly align with the axis of evil. Statistically, this happening based on chance alone is merely 0.04 percent likely.

According to Michael Longo (from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor), “This suggests the axis is real, and not simply an error in the WMAP data.” And for that fact, “We can be extremely confident that these anomalies are not caused by galactic emissions and not caused by instrumental effects, because our two instruments see very similar features.”

Now, here’s where it gets super weird. The CMB data seems to indicate that not only is there is some kind of a preferred direction for light in space to travel in — a conclusion based on the fact that certain galaxy clusters are speeding off at more than 2 billion kilometers per hour, all traveling toward an expanse of space that, relative to Earth, is merely 20 degrees in size (see above) — but this direction appears to correspond with the curvy “line” dividing temperature lobes in the CMB (and interestingly, it also seemingly coincides with the ecliptic plane of our solar system )

As for the “how” and “why,” astronomers posit that the axis of evil might indicate that there are issues with how we incorporate inflation — the period when the universe expanded exponentially in size in fractions of a second — into the big bang theory. Our models say that this expansion should have happened simultaneously in all directions, but what if it actually expanded more in one direction? And what if this is the reason for the abnormality?

“Provided inflation stops at a relatively early point, this would leave traces of the early [unevenness] in the form of the axis of evil,” according to one physicist.

Since these strange features were first witnessed in the CMBR by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), opinions in the scientific community have been divided. When asked whether or not “there are potential deviations from ΛCDM within the context of the allowed parameter ranges of the existing WMAP observations,’ they answered with a resounding “no,” but some of the naysayers have since changed their tune, following the release of data collected on the anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background by the ESA’s Planck Space Observatory. Still, as one researcher put it, “Human eyes and brains are excellent at detecting visual patterns, but poor at assessing probabilities.”

However, as the quantum world constantly reminds us, probability is a key part of the foundation of the universe.

APRIL 11, 2007 — ‘Axis of evil’ a Cause for Cosmic Concern?

“Some astronomers have suggested straightforward explanations for the axis, such as problems with WMAP’s instruments or distortions caused by a nearby supercluster (New Scientist, 22 October 2005, p 19). Others doubt the pattern’s very existence. “There’s still a fair bit of controversy about whether there’s even something there that needs to be explained,” says WMAP scientist Gary Hinshaw of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.”

[Reference: EurekaAlert]

SEPTEMBER 16, 2009 — Cosmic Cold Spot Just a Trick of the Light

“We trace this apparent discrepancy to the fact that WMAP cold spot’s temperature profile just happens to favor the particular profile given by the wavelet.” “We find no compelling evidence for the anomalously cold spot in WMAP at scales between 2 and 8 degrees.”

[Reference: MIT Technology Review]

FEBRUARY 9, 2010 — Seven-Year WMAP Results: No, They’re NOT Anomalies:

Since the day the first Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) data were released, in 2003, all manner of cosmic microwave background (CMB) anomalies have been reported; there’s been the cold spot that might be a window into a parallel universe, the “Axis of Evil”, pawprints of local interstellar neutral hydrogen, and much, much more. But do the WMAP data really, truly, absolutely contain evidence of anomalies, things that just do not fit within the six-parameters-and-a-model the WMAP team recently reported? In a word, no.

MARCH 12, 2013 — Planck Shows Almost Perfect Cosmos – Plus Axis of Evil:

“Planck reveals that one half of the universe has bigger variations than the other. Planck’s detectors are over 10 times more sensitive and have about 2.5 times the angular resolution of WMAP’s, giving cosmologists a much better look at this alignment. “We can be extremely confident that these anomalies are not caused by galactic emissions and not caused by instrumental effects, because our two instruments see very similar features.”

MARCH 21, 2013 — SIMPLE BUT CHALLENGING: THE UNIVERSE ACCORDING TO PLANCK

“Other anomalous traits that had been hinted at in the past – a significant discrepancy of the CMB signal as observed in the two opposite hemispheres of the sky and an abnormally large ‘cold spot’ – are confirmed with high confidence.”

[Reference: European Space Agency]

MARCH 09, 2014 — Is the Lopsided Universe Telling Us We Need New Theories?

“I think the alignment, in conjunction with all of the other large angle anomalies, must point to something we don’t know, whether that be new fundamental physics, unknown astrophysical or cosmological sources, or something else.”

[Reference: ARS Technica][/toggle]