Edo Kael

Dec 6 (4 days ago)

to Jim, don, Juan, David, jhafner, Buddy, Neil, Peter, frank

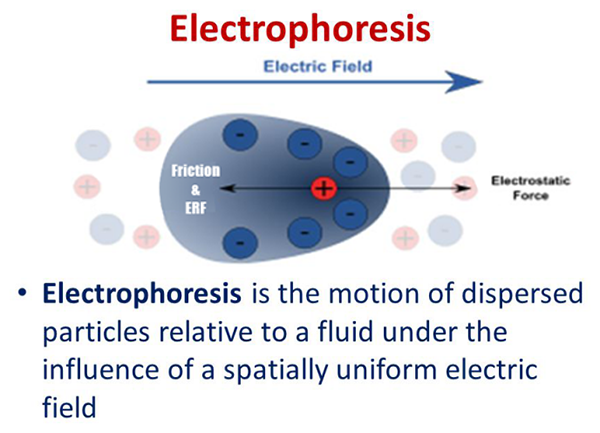

If I am understanding this correctly (and I might very not), then up to a certain (small) level the Magnetic forces are able to “push” alike particles i.e protons/electrons closer together.

The question fer me is if this is the same thing i tried to point out? I am inclined to see this as two different principles, One dictates by the larger on the smaller as you describe and the other one the intrinsic forces that are at play at a proton electron level. I am also inclined to believe that the smallest at first dictates the larger, although the other way around is very much there as well. Or.. are both always at play indeed….

Think we need another meet-up 🙂

Edo

On Tue, Dec 5, 2017 at 6:50 PM, Jim Weninger <jwen1@yahoo.com> wrote:

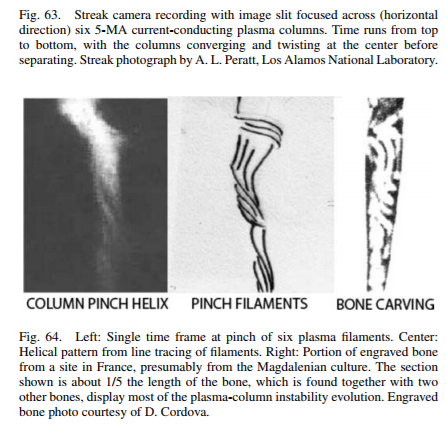

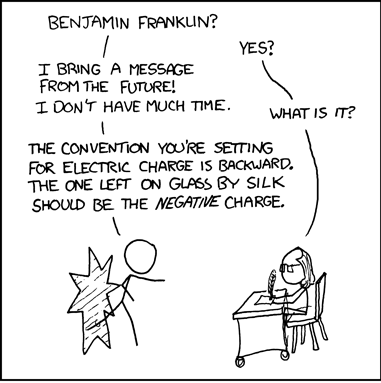

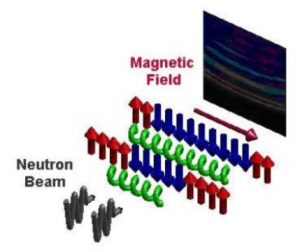

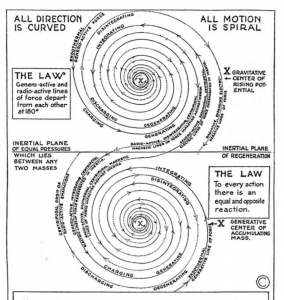

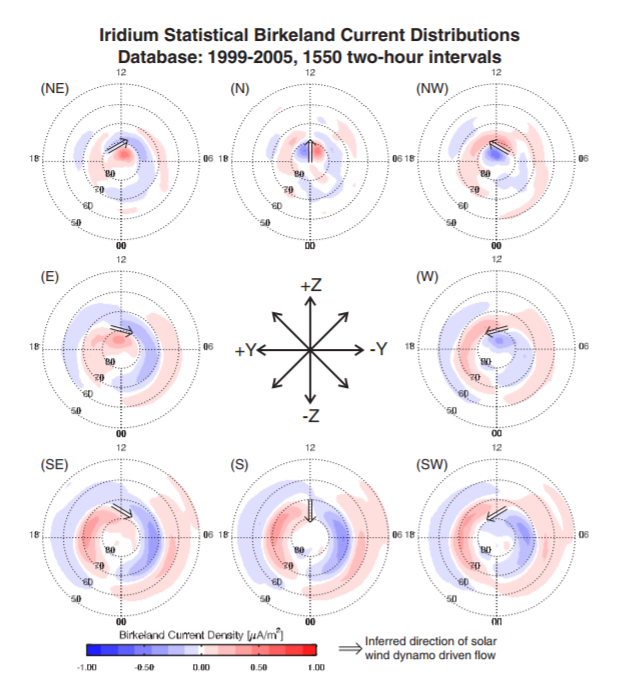

Not just electrostatics, but adding in magnetism, and we get what looks like a bizzarre mixture of long range and short range, attractive and repulsive forces.

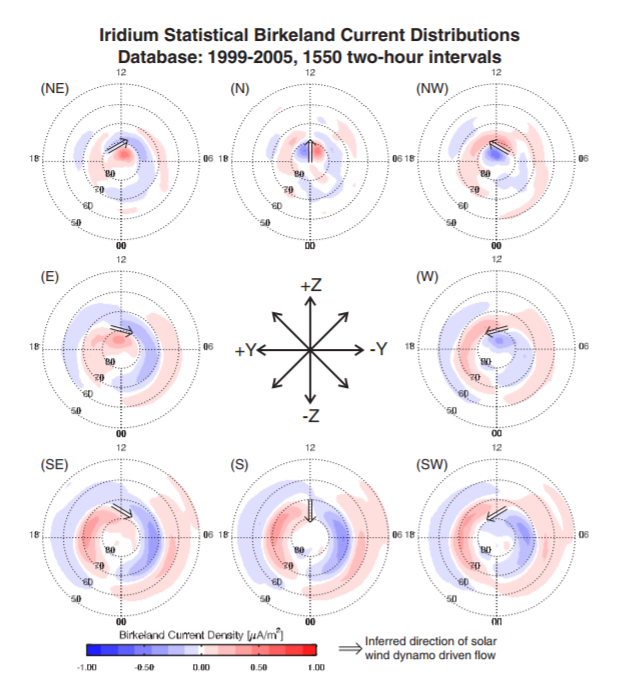

We know from Birkeland currents, that outside of a B.C., we should have electrostatic repulsion of like charged objects. Within the B.C., we have a binding of like charge, by the magnetic forces of the filament. The B.C. can sort charged matter into shells,but also force matter towards the central radius. The magnetic field of a B.C., does “turn off” at some radius, leaving us with again merely the electrostatic repulsion of like charges, now much higher because of the density of charged material forced to the center of the filament.

A mistake here, would be to forget about the filament (and resulting magnetic forces) in which the particles reside, and try to explain what we are seeing by radial forces between individual particles themselves. Notice that the effect of a B.C. is to push some charged material in to the center of the filament, but only until the radius where the magnetic field “turns off”, and we only have the electrostatic repulsion of like charges, so it appears that there is an attractive force, that suddenly become repulsive at some radius. There are no attractive forces involved ever. We have the Lorentz force pushing material in to the center, and where that turns off, only the repusive force pushing charge apart.

On Monday, December 4, 2017, 12:24:48 AM MST, Edo Kael <edwinkaal00@gmail.com> wrote:

From one of the links…..

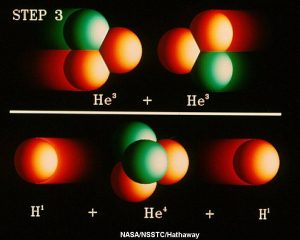

“….THE LOW-ENERGY NUCLEAR REACTION: SOME CALL IT COLD FUSION / REGARDLESS OF THE THEORETICAL EXPLANATION, SOME SAY THERE’S BY NOW NO DOUBT THAT NUCLEAR REACTIONS CAN BE TRIGGERED USING CHEMICAL ENERGY / ALTHOUGH THESE CLAIMED…

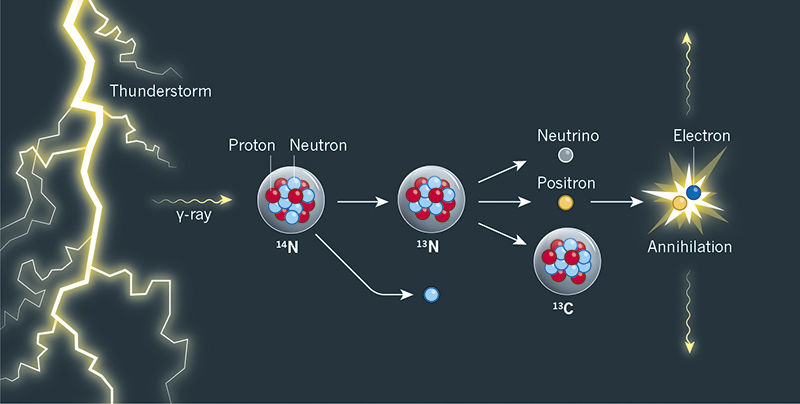

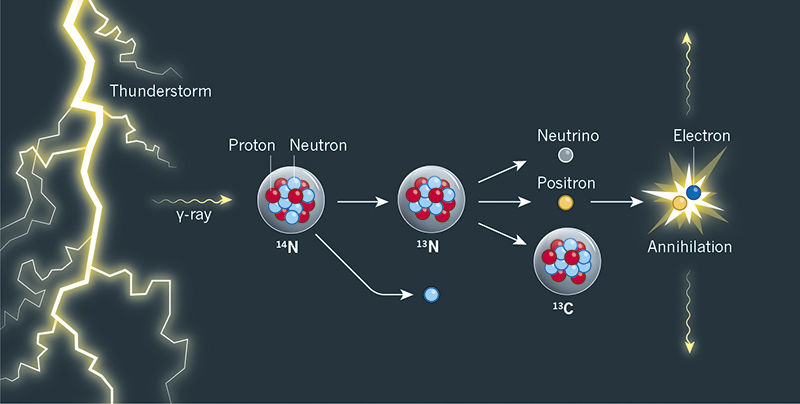

Thunderous Nuclear Reactions

|

|

|

|

|

to David, jhafner, Juan, Don86326, Peter, Edo, Lukas, Neil, Buddy, Jeff, jakechateauwork

|

|

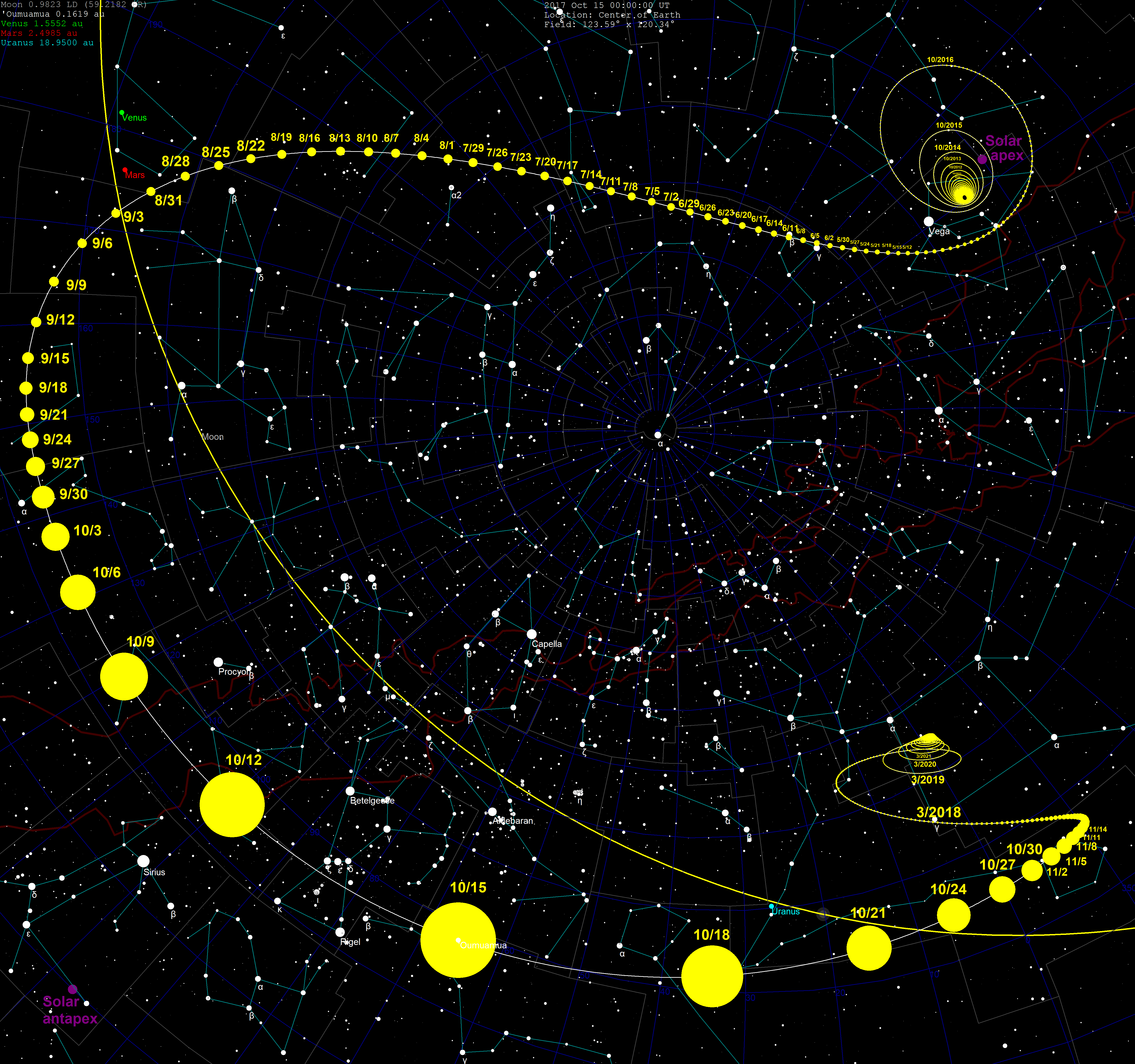

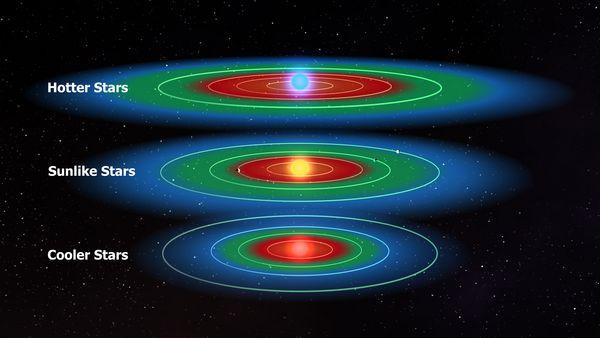

I would like to get a bit into the discrete qualities on the solar system scale, since Edo mentioned it.

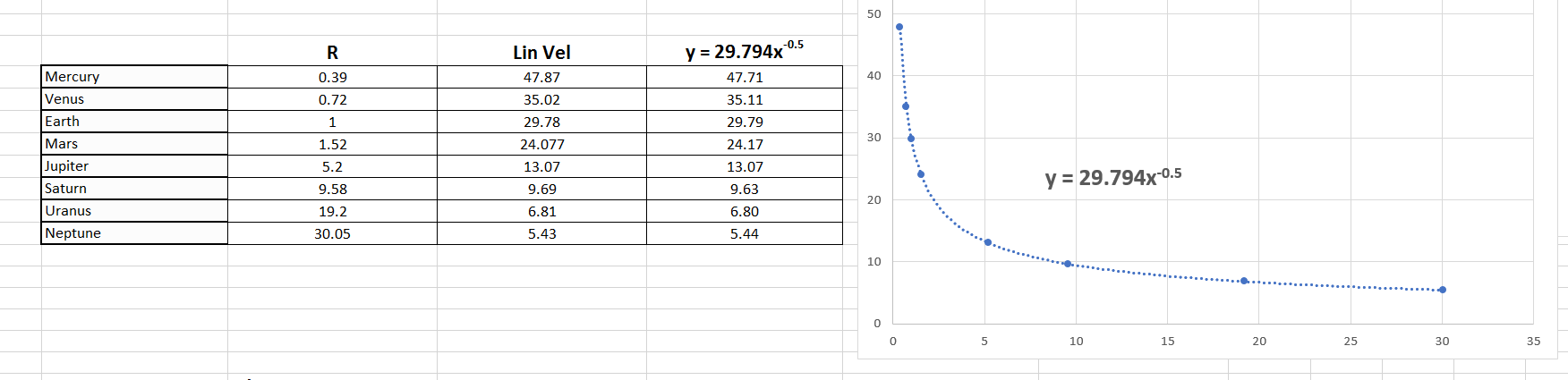

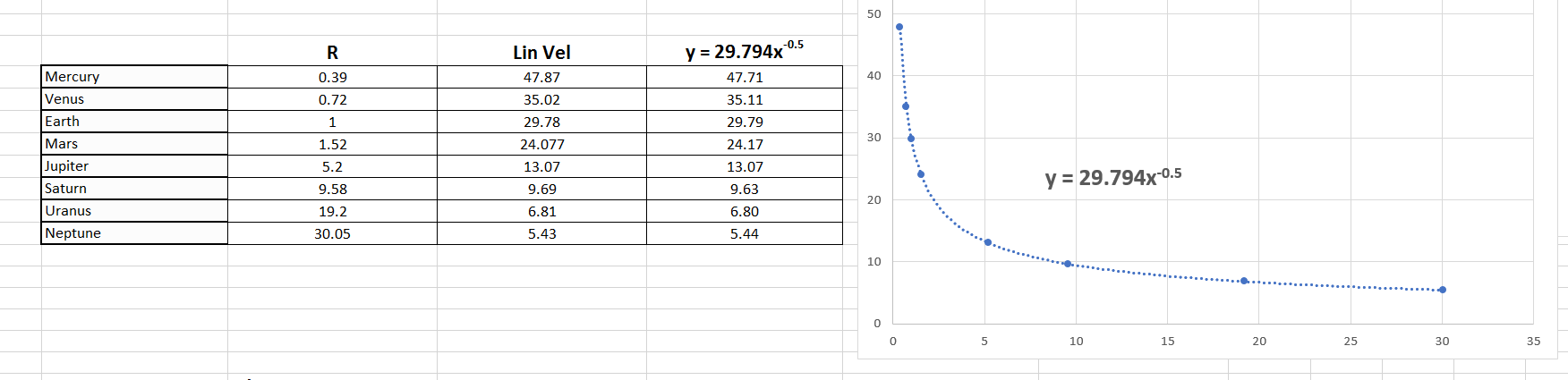

If one accepts Titius-Bode (and it does seem to work outside of just planetary orbits, has a mechanism in EU,etc), then that means that possible planetary radii do not form a continuous distribution, but form a discrete series of shells.

The significance of that, however, is that planetary orbital periods must also fall into discrete “steps”(Kepler’s third law), and masses too (the inverse square law that appears to work whether or not we agree on the mechanism). From those, you are forced to conclude that a planet’s velocity, kinetic energy, orbital potential energy, orbital angular momentum, etc, are also allowed to occur only in discrete steps. Yep,.. if Titius-Bode is correct, we can calculate all major orbital/energy properties of any additional planet that may be discovered, BEFORE it is discovered, and all using that Bessel function. So, maybe the idea of simplicity and quantization only being a property of the smallest scale, is an illusion after all?

Jim

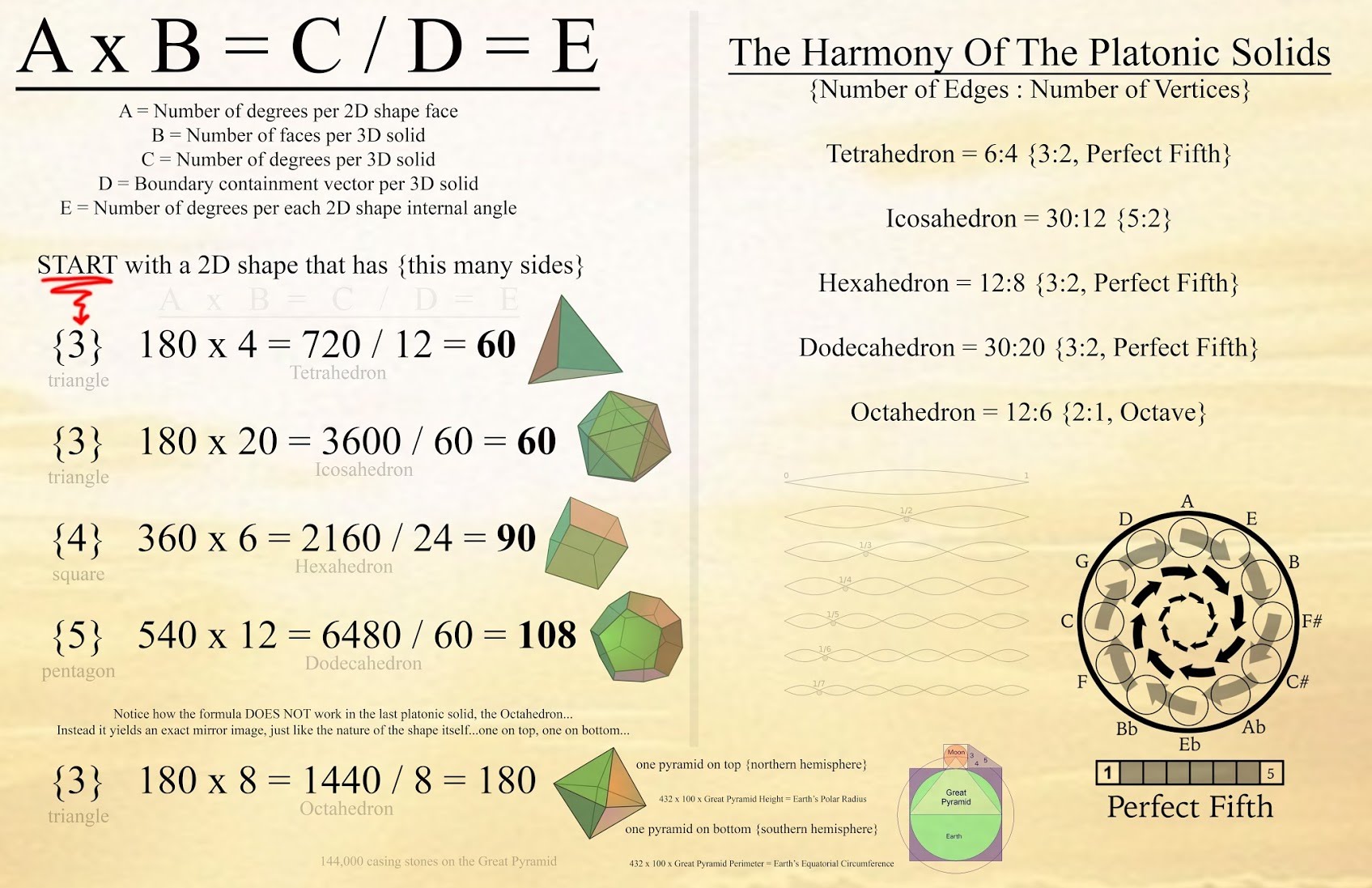

The Law of Harmonies

Kepler’s third law – sometimes referred to as the law of harmonies – compares the orbital period and radius of orbit of a planet to those of other planets. Unlike Kepler’s first and second laws that describe the motion characteristics of a single planet, the third law makes a comparison between the motion characteristics of different planets. The comparison being made is that the ratio of the squares of the periods to the cubes of their average distances from the sun is the same for every one of the planets. As an illustration, consider the orbital period and average distance from sun (orbital radius) for Earth and mars as given in the table below.

| Planet |

Period

(s) |

Average

Distance (m) |

T2/R3

(s2/m3) |

| Earth |

3.156 x 107 s |

1.4957 x 1011 |

2.977 x 10-19 |

| Mars |

5.93 x 107 s |

2.278 x 1011 |

2.975 x 10-19 |

Observe that the T2/R3 ratio is the same for Earth as it is for mars. In fact, if the same T2/R3 ratio is computed for the other planets, it can be found that this ratio is nearly the same value for all the planets (see table below). Amazingly, every planet has the same T2/R3 ratio.

| Planet |

Period

(yr) |

Average

Distance (au) |

T2/R3

(yr2/au3) |

| Mercury |

0.241 |

0.39 |

0.98 |

| Venus |

.615 |

0.72 |

1.01 |

| Earth |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Mars |

1.88 |

1.52 |

1.01 |

| Jupiter |

11.8 |

5.20 |

0.99 |

| Saturn |

29.5 |

9.54 |

1.00 |

| Uranus |

84.0 |

19.18 |

1.00 |

| Neptune |

165 |

30.06 |

1.00 |

| Pluto |

248 |

39.44 |

1.00 |

(NOTE: The average distance value is given in astronomical units where 1 a.u. is equal to the distance from the earth to the sun – 1.4957 x 1011 m. The orbital period is given in units of earth-years where 1 earth year is the time required for the earth to orbit the sun – 3.156 x 107 seconds. )

Kepler’s third law provides an accurate description of the period and distance for a planet’s orbits about the sun. Additionally, the same law that describes the T2/R3 ratio for the planets’ orbits about the sun also accurately describes the T2/R3 ratio for any satellite (whether a moon or a man-made satellite) about any planet. There is something much deeper to be found in this T2/R3 ratio – something that must relate to basic fundamental principles of motion. In the next part of Lesson 4, these principles will be investigated as we draw a connection between the circular motion principles discussed in Lesson 1 and the motion of a satellite.

How did Newton Extend His Notion of Gravity to Explain Planetary Motion?

Newton’s comparison of the acceleration of the moon to the acceleration of objects on earth allowed him to establish that the moon is held in a circular orbit by the force of gravity – a force that is inversely dependent upon the distance between the two objects’ centers. Establishing gravity as the cause of the moon’s orbit does not necessarily establish that gravity is the cause of the planet’s orbits. How then did Newton provide credible evidence that the force of gravity is meets the centripetal force requirement for the elliptical motion of planets?

Recall from earlier in Lesson 3 that Johannes Kepler proposed three laws of planetary motion. His Law of Harmonies suggested that the ratio of the period of orbit squared (T2) to the mean radius of orbit cubed (R3) is the same value k for all the planets that orbit the sun. Known data for the orbiting planets suggested the following average ratio:

k = 2.97 x 10-19 s2/m3 = (T2)/(R3)

Newton was able to combine the law of universal gravitation with circular motion principles to show that if the force of gravity provides the centripetal force for the planets’ nearly circular orbits, then a value of 2.97 x 10-19 s2/m3 could be predicted for the T2/R3 ratio. Here is the reasoning employed by Newton:

Consider a planet with mass Mplanet to orbit in nearly circular motion about the sun of mass MSun. The net centripetal force acting upon this orbiting planet is given by the relationship

Fnet = (Mplanet * v2) / R

This net centripetal force is the result of the gravitational force that attracts the planet towards the sun, and can be represented as

Fgrav = (G* Mplanet * MSun ) / R2

Since Fgrav = Fnet, the above expressions for centripetal force and gravitational force are equal. Thus,

(Mplanet * v2) / R = (G* Mplanet * MSun ) / R2

Since the velocity of an object in nearly circular orbit can be approximated as v = (2*pi*R) / T,

v2 = (4 * pi2 * R2) / T2

Substitution of the expression for v2 into the equation above yields,

(Mplanet * 4 * pi2 * R2) / (R • T2) = (G* Mplanet * MSun ) / R2

By cross-multiplication and simplification, the equation can be transformed into

T2 / R3 = (Mplanet * 4 * pi2) / (G* Mplanet * MSun )

The mass of the planet can then be canceled from the numerator and the denominator of the equation’s right-side, yielding

T2 / R3 = (4 * pi2) / (G * MSun )

The right side of the above equation will be the same value for every planet regardless of the planet’s mass. Subsequently, it is reasonable that the T2/R3 ratio would be the same value for all planets if the force that holds the planets in their orbits is the force of gravity. Newton’s universal law of gravitation predicts results that were consistent with known planetary data and provided a theoretical explanation for Kepler’s Law of Harmonies.

SpinBitz Joel D. Morrison

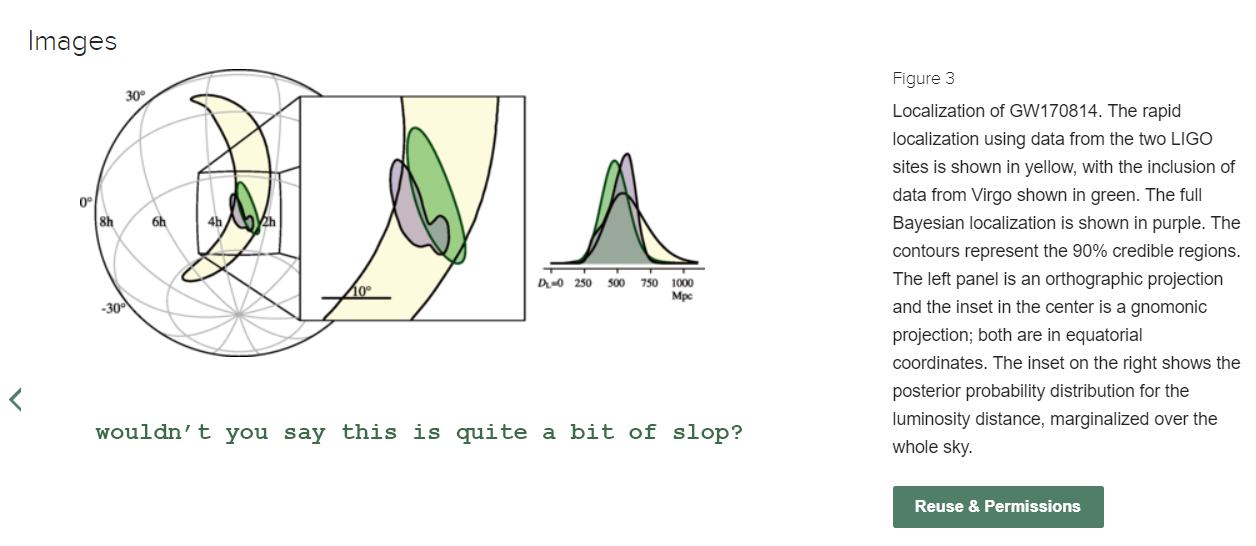

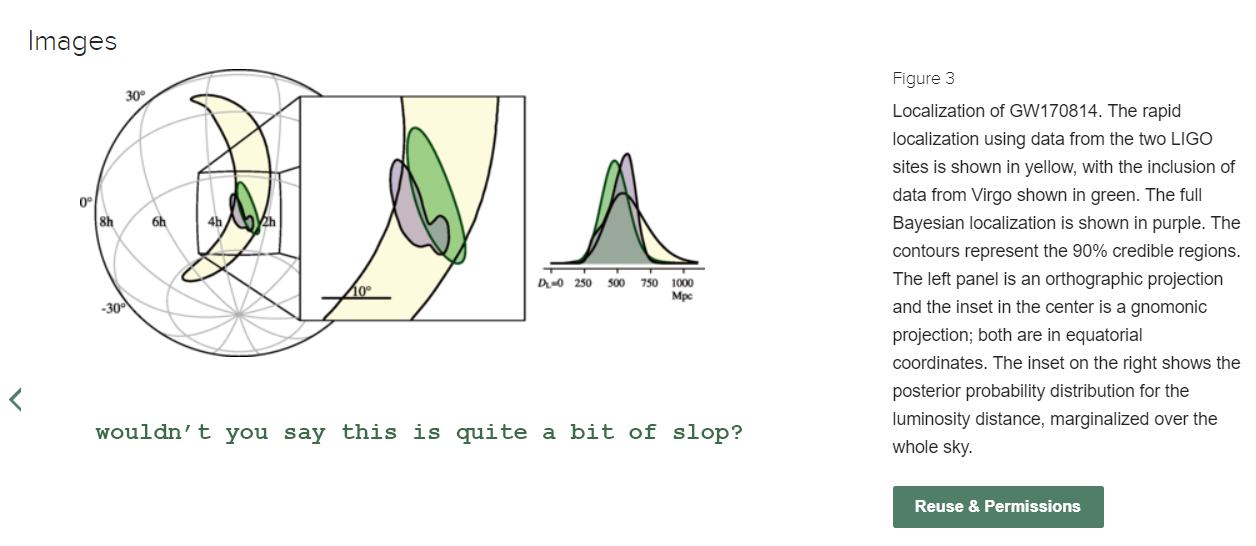

LIGO

https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.141101

https://www.space.com/25088-gravitational-waves.html

What are the Assumptions?